The Sixth Original Writing Competition

Junior High School Group

Platinum Award

Written by Tian Zimeng,

Qianjin Road Middle School, Weinan City, Shaanxi Province, China

Date: May, 2019

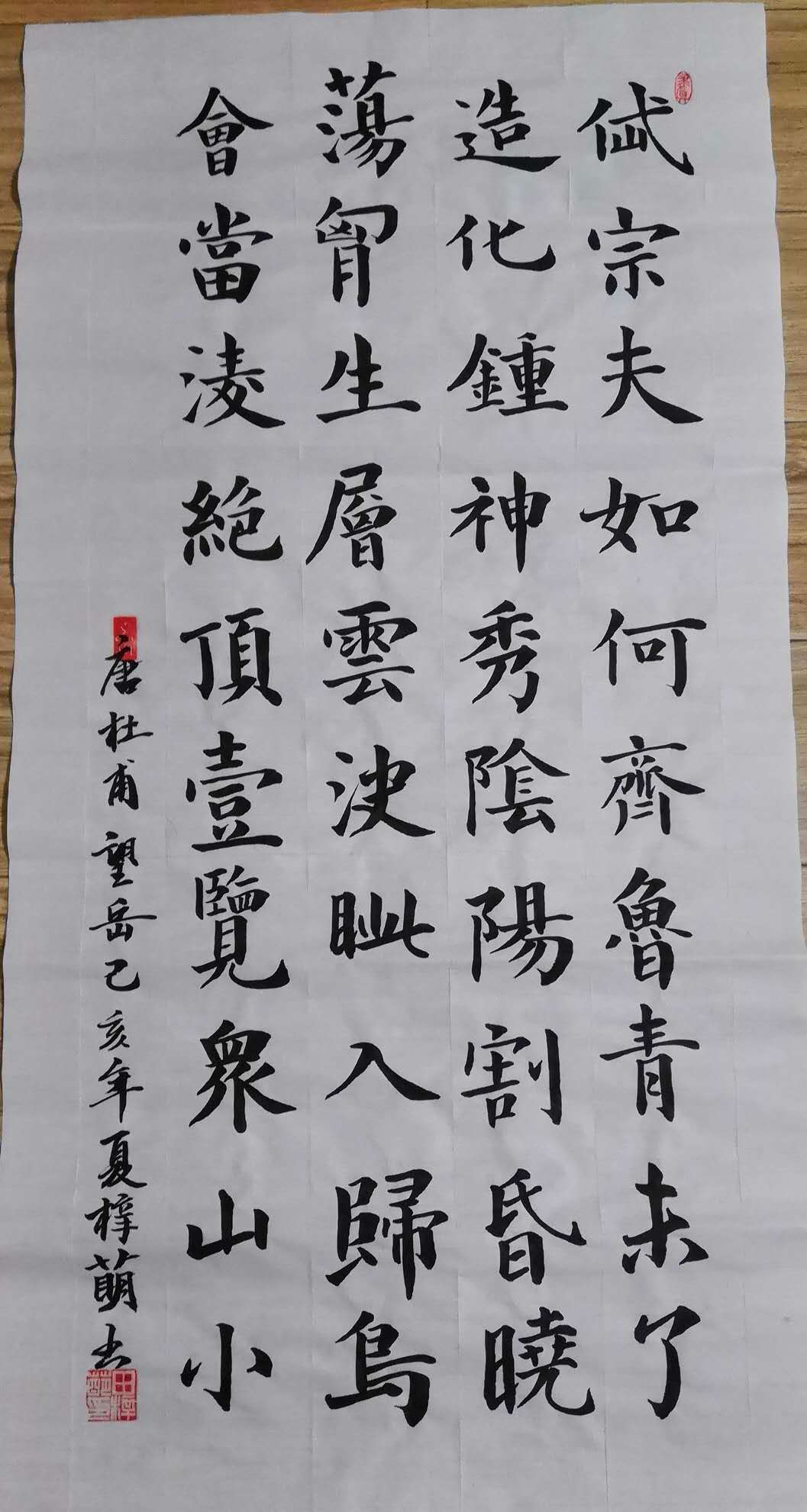

Did you know that wheat and sorghum grow here in the yellow earth? The people make their living on the banks of the Yellow River. Here also, an ancient city stands, a survivor through the ebb and flow of millennia. It was once a place of raucous nightlife; a place brilliantly illuminated from dusk to dawn. “The song lingered on” A Song of Immortal Regret; “A melody lingers on blustery winds; How may I dispel my woe? Only Dukang (The first brewer in Chinese history)

Here in Shaanxi, tempestuous fire meets with blood in a raging bonfire. Here was where the sounds and song of the Qin were first sown. For me, this is where life first began.

In early spring while walking home one weekend, I took to kicking small stones along the side of the road; once, twice, many times across the petal-strewn pavement as I progressed on my journey homeward. It was a sudden, low-pitched grumble that shook me from my apathetic stupor. My eyes turned in the direction of the noise, quickly settling on an older man. He was holding a microphone in his hand and, from his enervated expression and the sweat beading on his brow, I guessed that he had just finished singing. Others next to him had other instruments like the erhu fiddle, dulcimer, and banhu fiddle. After a short rest, the man again broke out in song in his powerfully sonorous and gravelly voice. In the moment, I felt myself transported to the banks of the Yellow River, its waters lapping solidly against the shore. Yes, she wanted to escape her confines. She was expending her energies, looking to carry those confining soils away bit by bit, to continue creeping forward. Finally, with another morsel of silt in hand, she high-tailed it away, leaving but frothy waves in her wake. I snapped out of my daydream to find that an enthusiastic crowd had already gathered around the old men. The wind had kicked up, sending cherry petals drifting slowly toward the waiting ground. I brushed the petals that had landed in my hair off and continued on my way. But what I had just experienced had sent ripples across my soul. I had just experienced Shaanxi opera – an art form born, nourished, and perfected by the people of Shaanxi. Shaanxi opera is part of me. It runs through the blood of all those who call Shaanxi home.

On an episode of the television variety show China Star, Tan Weiwei’s soft yet powerful rendition of a classic Huayin ‘Lao Qiang’ won accolades from all watching. Every sentence struck the heartstrings, taking the audience to the zenith of excitement. The first time I saw the broadcast was in fourth grade. After the song had finished, although I didn’t know how to describe it at the time, I knew that something more than blood was stirring deeply within my chest and infiltrating my very being. Qin’qiang is the forerunner of Shaanxi opera and both share much in common. Each requires singers to invest every ounce of their energy and being into each performance, revealing in the process the gregarious boldness that defines the people of Shaanxi as well as the unique, synergistic balance they have struck between rigidity and pliancy.

I remember one midsummer’s eve watching my grandparents assembling a metal bedframe in the courtyard. The evening breeze carried a medley of warm and cool air. Grandma kept mosquitoes and other bugs away from me with her large feather fan. I looked skyward to see if I could find the Northern Star I’d read about in my school textbook. Scanning the skies in vain, I finally dozed off on the pillow. Half asleep, I could still faintly hear my grandmother softly singing songs from “Third Mother Teaches Her Son” and “The Case of Chen Shimei”. I couldn’t fight the drowsiness and fell into a deep slumber. My dreams that night were crowded – Chen Shimei, Third Mother, Xue Guang, and others all showed up.

My grandfather is a true son of Shaanxi. He reflects the unrestrained, honest character that is typical of the people of this province. He drinks his wine by the bowlful and his meat by the mouthful. He talks in loud, strident tones paired with his highly expressive face and an unfalteringly lively stream of body language. Indeed, it may seem to the casual observer that our family was constantly quarreling. One of my most indelible memories is when Grandpa took me to a ‘dog chasing rabbit’ tournament on Shaanxi’s Guangzhong Plain. After a hearty meal, the villagers rode their motorbikes to the next village over for the rabbit-chasing event. As soon as the starting whistle blew, six breeders unclasped the leashes on their dogs, which took off at breakneck speeds. All started off in a close and evenly matched race before gradually spreading out until, finally, a clear winner emerged. One in the pack invariably grounds the rabbit first. Breaking the soft throat of its prey, the champion carried its trophy back to its master for praise and appreciation. The face of the winning breeder was, of course, beet red with pride. He laughed boisterously and gave a hearty shout, all while patting his prize pooch on the head. He could call over some of his best buddies to share in some wine and finger food or, if desirous of more, he could call for another contest to be run. After this rousing day of activity, I returned to our village around dusk to wisps of smoke curling from chimneys, dogs barking in the streets, and sounds of laughter echoing from warmly lit homes, some of which, I could hear, had televisions tuned into that evening’s Shaanxi opera performance.

There is power in the zest for life, in the soil, and in the people of Shaanxi. It burns in the heart of every son and daughter of Shaanxi and builds into a cascade of brilliant sparks. These sparks come from the interplay between Shaanxi’s people and its opera, between Shaanxi’s people and their poetry, between Shaanxi’s people and their dog-chasing-rabbit tournaments and, most of all, between Shaanxi’s people and the region’s yellow soil. The Yellow River trickles across the land here. Bai Juyi once walked across this land. Dukang slipped into a pleasant, drunken haze here as well.

“I love San-Qin (Shaanxi), I love San-Qin.” After a busy day’s work, an article on Shaanxi opera in the back of the Dushikuaibao once more electrified the people of Shaanxi. The sentiment of “His first uncle and second uncle are both his uncle. The high table and simple stool are all made of wood” have once more been written by the people of Shaanxi.

Reviewer 1

Shaanxi opera, rooted indelibly in the passions and soil of Shaanxi, reflects well the rough and rugged nature of Shaanxi’s people. The interplay between Shaanxi opera and those living in the province creates the sparks that are this essay’s grandiloquent ‘detonator’. Bold and confident, chivalrous and big-hearted – all can be found in Shaanxi opera, giving this art form its sublime, transcendent allure.

Reviewer 2

The author deftly uses parallelism, conversion, hyperbole, contrast, and concise descriptions and employs words and phrases that capture well the desired ambiance of brash boldness. The powerfully sonorous Shaanxi opera intertwines with roiling river waters to stirring effect. The contrast between grandfather’s stern and grandmother’s soft natures enliven and give dimension to the essay. The description of the dog-chasing-rabbit tournament is thrilling, and well contrasted with the smoke-embraced village at dusk. The authors interlaced descriptions of the dog carrying its prey back to its master, the celebratory laughter, and Shaanxi opera brings Shaanxi’s folk culture alive to readers, making them eager to experience these things for themselves.